The Bundadhaany/Bunda-dyne/The Artist

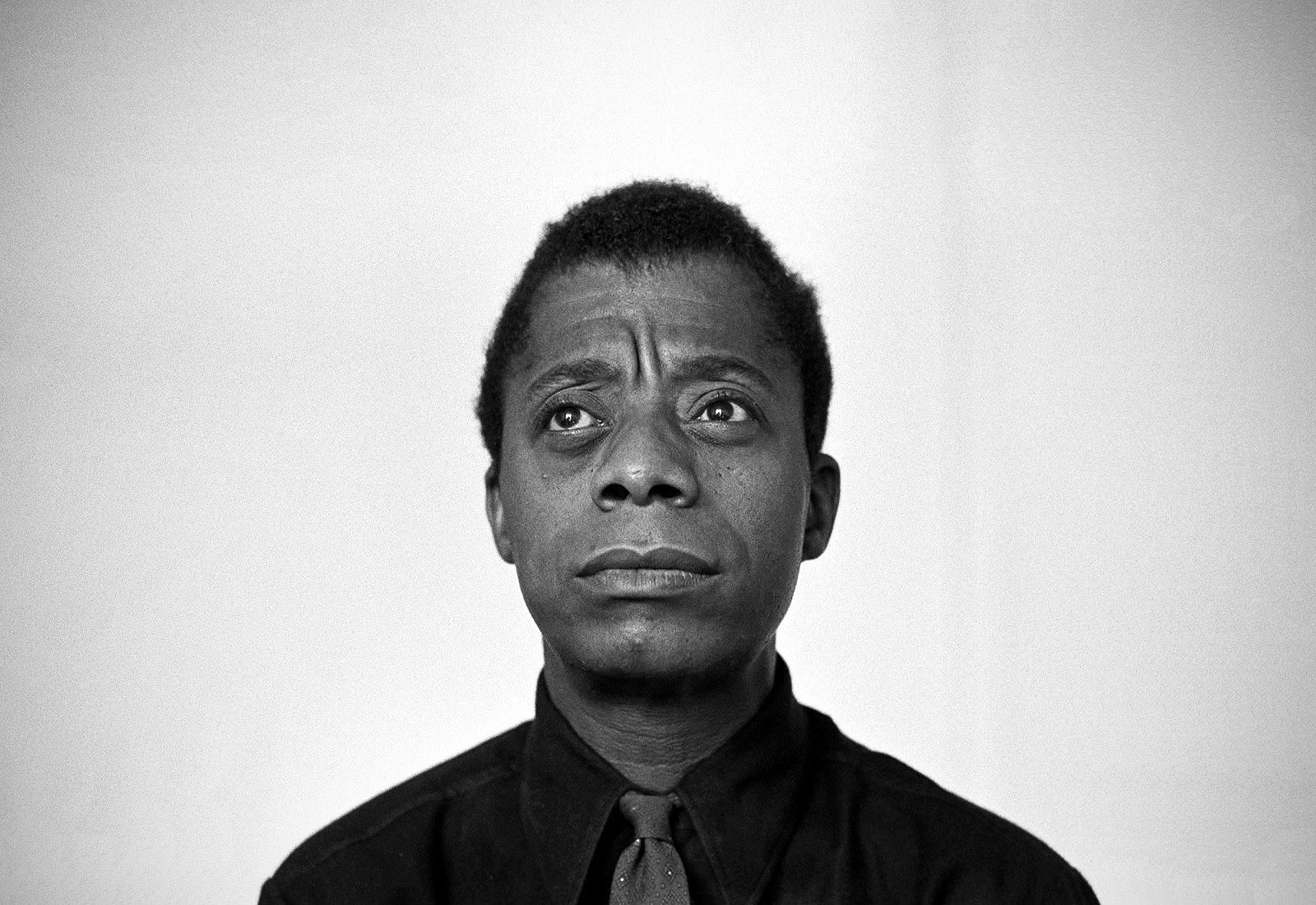

For James Baldwin, on his 100th birthday.

August 2024

The bundadhaany's work hung in the brightly lit rooms of a medium-sized public gallery somewhere on the edge of an indistinct settler-colonial city. The prints were intricate, beautiful, and deeply personal, each handworked detail embedding the work with his heritage, identity, and existence. He had poured his soul into this exhibition, believing, perhaps naively, that the gallery would understand the weight of his work and the stories woven into each piece.

But the gallery did not understand. They did not see the depth of the narrative, the cultural threads holding each piece together. To them, it was just another diversity exhibit to add to their roster, another show to fill their walls. They altered the exhibition without consent, removing crucial elements meant to guide viewers, to offer them a glimpse into the world the bundadhaany—a queer, Wiradyuri man—was trying to share. Stripped of these elements, his work was left hanging in the sterile space, reduced to a series of unanswered questions.

He realised the changes had been made on Instagram after the fact, without his input or any discussion. It was a cold, dismissive act, leaving him feeling silenced in the very place where his voice was supposed to matter.

He tried to reach out to communicate his concerns. Messages went unanswered, and calls were unreturned. The gallery moved forward with its plans, oblivious to the frustration and isolation tightening around the bundadhaany. His work and passion were reduced to mere decoration—something to be observed, not understood.

The gallery's promotion of the exhibition was another blow. Images of the work were distorted, titles incorrect, narrative lost. The gallery seemed to say, "Your story is not worth telling as it is. We will reshape it to fit our needs and our comfort."

When he finally managed to speak with the gallery's representatives, the conversation bordered on absurdity. They praised his exhibition, yet their words contradicted their actions, every apology an empty dismissal. The gallery prided itself on being a culturally safe space, a beacon of inclusivity, but its actions belied another story.

One incident laid bare the gallery's profound misunderstanding of cultural protocols, revealing the chasm between their claimed inclusivity and actual practices. When the bundadhaany asked for help connecting with a local Elder to discuss the appropriate use of language in his work, the gallery misunderstood. They assumed he wanted a Welcome to Country ceremony—something entirely different.

The bundadhaany's frustration deepened. They had conflated two distinct cultural practices, reducing his simple, respectful request to a formality. The gallery's response revealed how little they understood or cared to understand. This confusion was not an isolated mistake—it was symbolic of their superficial engagement with his culture, reducing deeply meaningful practices to mere formalities.

The bundadhaany listened as they blamed logistical issues, communication errors, and unnamed external pressures. They spoke of avoiding "derailments," as if protecting the work from controversy was more important than preserving its integrity.

"Derailment." The word hung in the air, heavy with implications. Clearly, they weren't protecting his work; they were protecting themselves. Baldwin's voice echoed in his mind, reminding him that such dismissals were not mere ignorance but willful blindness—a refusal to confront the uncomfortable truths of power and culture.

"But it's been derailed by you now," he said, his words carrying the weight of his anger and exhaustion. "Removing the essential visual reference negates the work’s entire purpose."

Their response was more of the same—a mixture of condescension and hollow assurances. "We should have had a conversation with you, absolutely," they admitted, yet their tone suggested they still believed their actions were justified. To them, his work was something to be edited, censored, and controlled to fit a narrative that was not his own.

But the bundadhaany knew better. The gallery's actions were not just poor communication or oversight. They resulted from a system thriving on control, silencing voices that challenged the status quo, and rewriting narratives to fit a comfortable mould. His work, his identity, was not a derailment—it was the truth the gallery refused to confront.

As he reflected on the conversation, the bundadhaany saw the broader pattern—an echo of colonial dynamics where institutions claimed to celebrate diverse voices but, in reality, sought to control and assimilate them. The gallery's actions were not just about this one exhibition—they perpetuated a system that valued control over creativity, prioritised the institution over the individual, and maintained the power dynamics of colonialism under the guise of inclusivity. In its polished halls and sterile walls, the gallery was a microcosm of a larger structure that continued to marginalise and silence, even as it professed to uplift.

The bundadhaany's resolve hardened. He would take a stand, not just for himself, but to ensure that no one else would endure the same experience. He would demand respect for his work, his culture, and the voices of others who might come after him. His battle was not just for his own integrity but for all those who had been, or could be, marginalised, silenced, and reshaped by a system that sought to control rather than uplift.

The bundadhaany felt a welcome calm as he walked from the gallery. He had faced the absurdity of his situation, seen it for what it was, and chosen to resist. In that moment, he found meaning—a reason to continue creating, to keep making his story, even if the colony refused to listen. James Baldwin's words rang true—"The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place." And in that struggle, the bundadhaany found his strength.

Clinton Hayden is a Wiradjuri Blak queer artist and writer based in Melbourne. His practice spans photography, AI image creation, print media, drawing, and bricolage, exploring the intersections of personal and collective histories. Clinton’s work is deeply informed by his commitment to preserving and promoting Wiradjuri language and engaging with Indigenous Queer Futurism.